Download this text as PDF-file

BACKGROUND PROFILE

POLISH-UKRANIAN CASE STUDY

SUMMARY

Department of Economic Geography, University of Gdansk , Poland

POLITICAL BACKGROUND

The Polish-Ukrainian cross-border areas share a long common past, despite separation after World War. After 1945, the region was divided between Poland and the Soviet Union. From this time on, and until the political and economical changes at the turn of the 1990s, the new borders were basically closed, making relations between Ukraine and Poland limited to interaction at border crossing points. With the collapse of the Warsaw Pact, Poland focussed its attention on relations with the West, on prospects of North Atlantic Treaty Organization membership and integration into the European Union. After the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, and the subsequent proclamation of independence of Ukraine, Poland was the first country to recognise Ukraine as an independent state and to recognise its borders. It was the moment when mutual relationships and cross border cooperation of both countries started to develop.

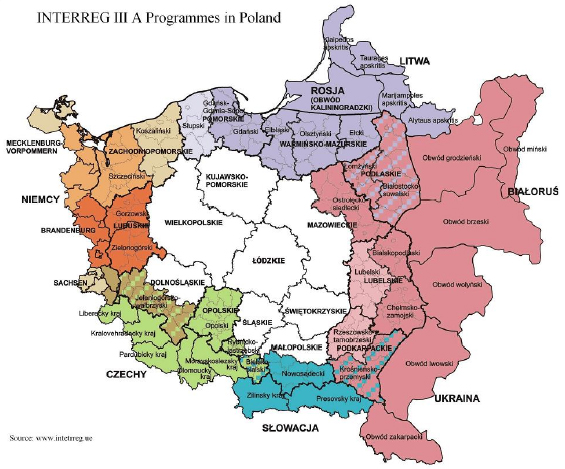

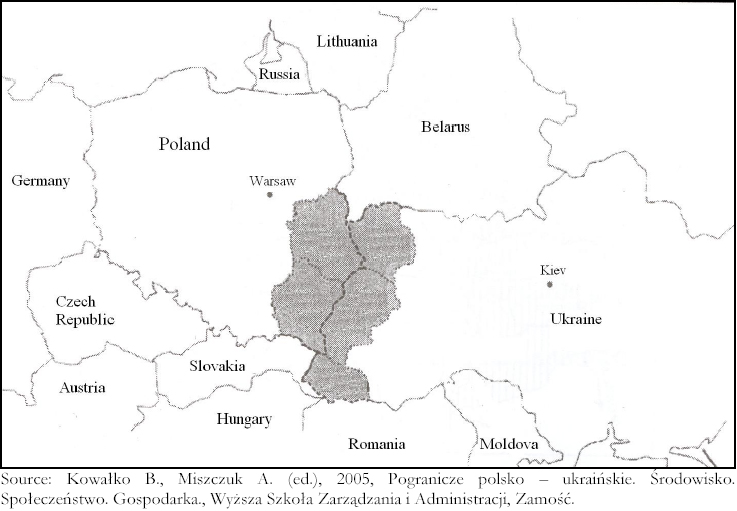

At present, the Polish-Ukrainian cross-border area includes four administrative units on the regional level (NUTS II): The voivodships Lubelskie and Podkarpackie on the Polish side and the oblasts Lwowska, Wolynska and Zakarpacka on the Ukrainian side. It covers an area of 97, 7 thousand km and comprises 9,2 million of inhabitants (4,3 mio. in Poland and 4,9 mio. in Ukraine). In terms of demographic issues both parts of the region are similar. Increasingly unfavourable social phenomena on both sides of the border contribute to depopulation and a weak economic basis. Economically speaking, the region as a whole is weaker than both the Polish and Ukrainian averages. Agriculture dominates. It is, however, worth to mention that significant differences exist between Poland and Ukraine in general. In the year 2002 the gross domestic product per inhabitant in Poland was six times higher than in Ukraine.

Ethnic minorities - because of assimilation policies in Poland and the Soviet Union – make up only a small share of today’s population in Poland and Ukraine. According to the Population Censuses only 5% of the cross-border area’s population belongs to an ethnic minority. On the Ukrainian side approximately 3% are Russians, 1% Polish and 0,2% Belarusians. On Polish side the dominant national group after Poles are Ukrainians, numbering 3,5 thousand (circa 1 %). Other national groups in the Polish areas are Russians and Belarusians.

In the past, contacts on the governmental level between Poland and Ukraine in the area of cross-border cooperation were limited to border security and, to a lesser degree, environment protection and transport matters. The Polish – Ukrainian border is crossed mainly by persons dealing with cross-border trade and, increasingly, by large number of illegal immigrants. It is one from main immigrants flow routes from Asia to Western Europe countries and source of illegal workers for the European Union.

Due to Polish EU accession on 1 January 2003, the Polish government introduced visa restrictions for all citizens from eastern neighbouring states, including Ukraine. However, to support border cooperation the Polish government also introduced preferential visas (cheaper and with longer empire date) for Ukraine and Kaliningrad inhabitants and extended consular points net. On the Polish – Ukrainian border solution is: free of charge visas for the Ukrainians and with assumption of no visa requirement for the Poles. At present, the number of border crossing points at the Polish-Ukrainian border is too low for the efficient handling of border traffic flows of goods and people. All 12 border stations are equipped with only inadequate infrastructure.

DIMENSIONS OF BORDER REGION CO-OPERATION

After 1991, conditions for Polish-Ukrainian cooperation at the governmental level radically improve. Since then Poland and Ukraine have signed a number of treaties and agreements that provide frameworks for international, interregional and cross-border cooperation in large number of areas. These include: border infrastructure, spatial planning, transport, municipal governance, industry, trade, agriculture, nature and natural environment protection, education and profession education, Polish and Ukrainian language education as a second language in schools (especially in cross-border areas), culture and art, health care, tourism, sport, information in the case of disaster prevention and other areas.

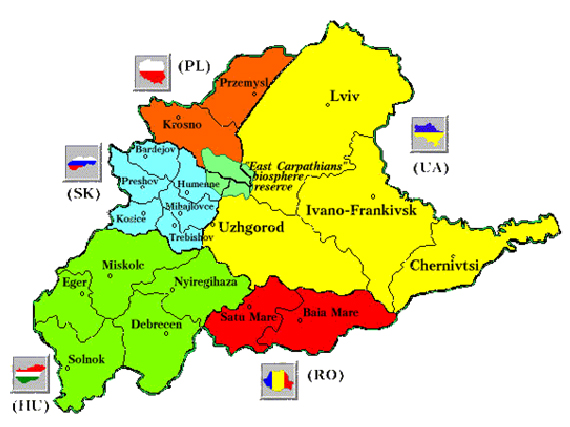

Cross-border co-operation, has been stimulated by a desire to improve economic prospects this peripheral border regions but also as a political signal of a more general “Europeanisation”, especially on the Ukrainian side. Economic cooperation between Poland and Ukraine in terms of general foreign trade is weak. It is also difficult to talk about any production cooperation between enterprises in the border region. Together with regional and local self-governments, non-governmental and social organisations have joined forces to create Euroregions in order to pursue goals of economic and wider societal development. Presently, two such organisations operate within the binational context: the “Carpathian” and “Bug” Euroregions. Their actions concern a wide range of concerns. However, critics claim that these cooperation associations have been more focused on obtaining funds for projects than politically supporting mutual cooperation.

The main possibilities for funding cross-border co-operation have, of course, been EU programmes such as INTERREG/TACIS. Polish-Ukrainian cooperation border will in future be funded through the EU’s Neighbourhood Programme for Poland-Belarus-Ukraine. Support within the framework of this program will be focused on, among others, security issues, increasing the competitiveness of the border area, the development of cross-border infrastructure, developing human capital and improved institutional conditions cross-border cooperation.

Contacts between non-government organizations are important in the Polish-Ukrainian binational context and they have increased both in numbers and fields of cooperation. At present their activities concern education, culture, the support of local governments in crossborder projects, training, humanitarian aid and social welfare, ecology and political development. Nevertheless, in terms of local/regional cross-border co-operation per se, small-scale activities such as petty trade and tourism have been dominant. Authorities indicate that formal co-operation is still at a preliminary phase of development. In spite of this, conditions for cooperation remain promising. And while actual cross-border related initiatives at the local level seem to be more of geopolitical than economic significance, they underline the fact that Poland and Ukraine recognize each other as strategic partners. There remain a number of barriers and problems in cross-border cooperation. The main problem lies in socio-economic and administrative asymmetries as well as in marked differences between Poland’s and Ukraine’s economic and regional development policies. For example, local governments on the Polish side are relatively autonomous in defining regional and local policies of a binational nature. Their counterparts in Ukraine, on the other hand, lack such autonomy and are obliged to seek central government approval for cross-border co-operation activities. Problematic on the Ukrainian side as well are unequal access to funding and a low level of institutional capacity for actually managing larger co-operation projects.

As part of the run-up to the 2007 introduction of the European Neighbourhood Programme, Poland and Ukraine have emphasised the importance of economic development and modern border infrastructures. However, co-operation in field of social integration, civil society and social infrastructure development also clearly requires greater material and political support. Thus it remains important to provide greater incentives and institutional supports to crossborder activities at the local and regional level. Indeed, the two sides agree that the border should be a bridge, even through it seems unlikely that a relaxation of border controls is even a remote shot to mid-term possibility. On a more positive note, however, It appears that mental barriers to co-operation are disappearing, despite technical issues and requirements to “securitise” the EU external border.

Figure: The Polish-Ukrainian cross-border area.

Source: http://www.euroregionbug.lubelskie.pl/

Picture: Euroregion Carpathia.

:

:

Source: http://www.karpacki.pl/