Download this text as PDF-file

BACKGROUND PROFILE

FINNISH-RUSSIAN CASE STUDY

SUMMARY

Karelian Institute, University of Joensuu, Finland

POLITICAL BACKGROUND

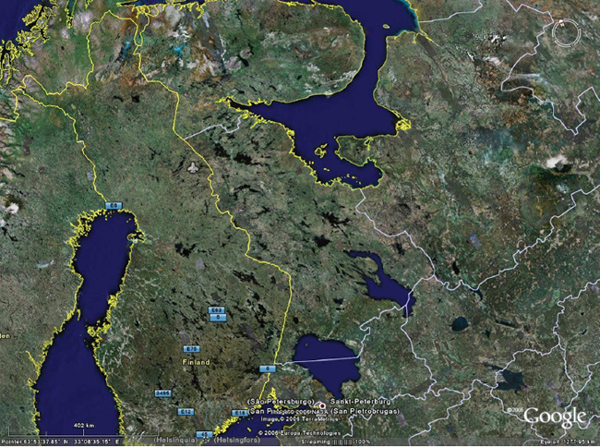

Throughout its history, the border that today separates Finland and the Russian Federation has experienced constant transformations and gained a number of different roles and images, most popular of which has been its function as a grand dividing line where East meets West. The 70-year-long closure of the border, from the aftermath of the Finnish independency until the collapse of the Soviet Union, had various implications, some of which seem to be more persistent than others. The socio-economic gap, as an example, that exists at the border ranks high even in global comparison.

The border has occupied its current position since the Peace Treaty of Paris in 1947. The situation that we see today derives, however, principally from two more recent factors: the disintegration of the Soviet Union in 1991 and the 1995 enlargement of the EU when Finland, along with Sweden and Austria, joined the union. Simultaneously, the Finnish-Russian border became the very first land border between the EU and the Russian Federation and drastic transformations took place in the border environment. The influence of these transformations on the geopolitical and geo-economic setting at the border has had profound impact on the life of the people inhabiting the border regions. As a result, the role of the border has been re-defined in several important respects. Although it is still strictly and effectively controlled, “room for regionality” has been created in the political landscape and required technical infrastructure such as crossing-points have been constructed. This has led to the emergence of new forms of interaction at various spatial scales. The establishment of Euregio Karelia in 2000, between the Republic of Karelia and its neighbouring regional councils in Finland, is a concrete example of these developments.

In geographical terms, the Finnish-Russian border does not follow any clear cut natural barriers to human interaction. The total length of the border, from the Gulf of Finland to the high north almost up to the Barents Sea, is more than 1300 kilometres. For most part it runs through forests and extremely sparsely populated rural areas; the metropolis of St. Petersburg at the distance of about 150 kilometres from the border being the only notable exception. The total number of population living on the Finnish side in the municipalities (NUTS 5) sharing the border with the Russian Federation is 276 000. At the NUTS 4 level, the respective figure is 479 000, and at the NUTS 3 level 1.14 million (2005). Population concentrates in southern part of the border, where also the largest cities in the border region locate. A common character for the whole border region is that it loses population continuously; the few exceptions are Joensuu and Lappeenranta regions. On the Russian side, the total number of population in the three border regions (Leningrad Region, Republic of Karelia, and Murmansk Region) is 3.27 million while St. Petersburg with its 4.63 million inhabitants is a separate administrative unit inside the Leningrad Region. The uneven territorial distribution of population and economic activity is an important conditioning factor for cross-border interaction as well as regional development.

Eastern Finland can be regarded as a textbook example of the region, which has suffered from its location next to a closed border. Its production structure has been dominated by the forest sector. Even though the employment of the sector has declined during the last decades, the pattern is still visible in the production structure: the share of primary sector is considerably above the national average in the more northern part the border region, whereas the south-eastern part relies on heavy industries, in which paper and pulp production plays a major role. At the NUTS 4 level, the main differences follow the urban/rural division. Against this background, the change of border regime after the collapse of the Soviet Union resulted in positive anticipation in the beginning of the 1990s. The expectations of economic growth and structural renewal only materialised to a limited degree.

DIMENSIONS OF BORDER REGION – NORTHERN DIMENSION AND CO-OPERATION

The collapse of the Soviet Union paved the way for the redefinition of Finland’s place in the world. Free from the fear of Soviet influence, Finland was allowed to pursue towards goals that were considered to match better with the Finnish interests. Finland recognised the Russian Federation as the successor to the Soviet Union and was quick to draft bilateral treaties of goodwill between the two nations. The co-operation began also to acquire new forms, most of which would have been unthinkable during the Soviet times. Private companies pursued cross-border business activities and tourism, and public sector’s crossborder co-operation initiatives created new kind of interaction across the border, during these very first years of the open border.

After Finland joined the EU in 1995, its Russian policy has been carried out on two levels, through bilateral relationship and through participation in the formulation of EU policies towards Russia. The EU-Russia relationship is based on a Partnership and Cooperation Agreement (PCA), which was signed in 1994 and entered into force in 1997. A further development of EU-Russia relations led to an adoption of the EU Strategy towards Russia and a Russian Strategy for policies towards the EU in 1999. In 2003, the EU and Russia agreed to reinforce their co-operation by defining the long term four ‘common spaces’. A single package of Road Maps for the practical implementation of the four Common Spaces was then adopted in 2005. Today, Russia is an important partner with which there is substantial interest to engage and build a strategic partnership in all levels.

Particularly important to the development of the border areas is the elaboration of the initiative of the Northern Dimension of EU policies. Instead of being dealt with hard geopolitics, the border has been softened and “deproblematised”, perhaps even depoliticized. The aim of the central governments is to utilize the border rather as an active resource for local and regional social actors who perceive the border and its future in the light of everyday cross-border interaction.

The opening of the border, most importantly in the form of new crossing points, has facilitated a rapid increase in the total volume of cross-border traffic. The number of border crossings grew from less than a million in 1990 to approximately 6, 5 million people in 2005. Trade and investments have not, however, increased in a similar stable manner. Since the early 1990s, the share of Russian passengers has increased from 32 per cent to 60 per cent. Currently, a vast majority, approximately 75 per cent (close to five million per year) of the border crossings occur at the border of the Leningrad region, 23 per cent at the border of Republic of Karelia, and two per cent at the border of the Murmansk Region. A great deal of the border traffic consists of short-term visits for buying low-cost commodities, petrol and tobacco. After joining the Schengen agreement in 2001, Finland’s visa policy has become identical with the Schengen visa policy. Increasing cross-border interaction and linkages between regional actors of Finland and North-West Russia have brought the two sides closer to each other, generated new interaction and, to some extent, contributed to the formation of a new identity, re-territorializing the border as a consequence. These discourses do not only tend to abolish the mental border between “us” and “them”, they also foster a re-orientation of sub-national interest outwards, towards the EU. This nascent transborder regionalism between the Finnish and the Russian border regions, and especially its contribution to the process of “debordering”, has not, however, been utterly in line with the Russia’s federal leadership’s policies. President Putin’s federal reform in 2000 was designed to reinforce the “vertical of state power” in order to standardize federal relations defined bilaterally under the Jeltsin-period.

In general, both Finnish-Russian and the EU-Russian relations have remained peaceful and calm. Apart from the slowly rising debate on possible NATO membership in Finland, no ‘hard security’ issues have been on the table. Lately, trade between the two countries has grown fast. The border area has, however, faced a number of socio-economic concerns. Social and economic development in Russia has caused concerns among Finns and affected crossborder cooperation Social and economic development in Russia has caused concerns among Finns that economic and social problems might spread across the border to their own communities. These fears, whether based in fact or not, have affected institutional crossborder interaction. For this reason, mediating activities by Finnish, Russian and other civil society organisations are becoming an important element in community development and cross-border co-operation.

The Finnish-Russian Border Region

Satellite image of Finland and Northwest Russia