Download this text as PDF-file

BACKGROUND PROFILE

THE ESTONIAN-RUSSIAN CASE STUDY

SUMMARY

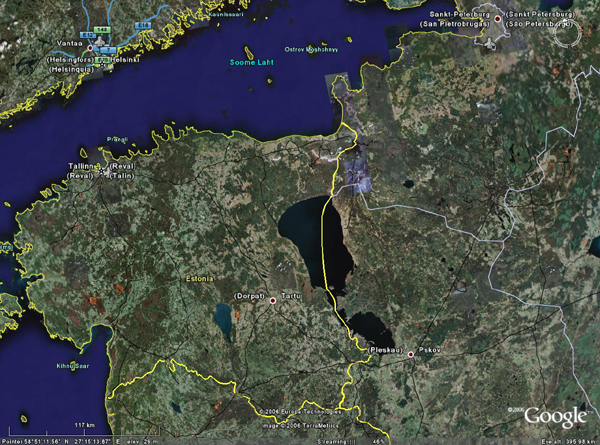

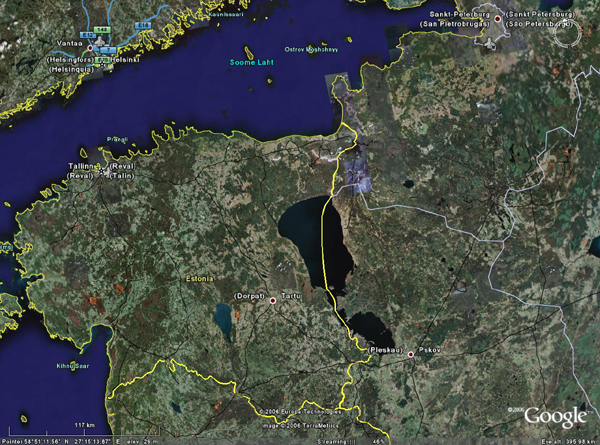

Estonia and Russia share a 230 km long border, the major part

of which is made up of the Lake Peipsi. The regions in the Estonian borderland,

Ida-Virumaa in the north-east, and Põlvamaa and Võrumaa in the south-east, are

some of the poorest in the whole country. The south-eastern regions are largely

rural, while the north-east is predominantly industrialised and urbanised. On

the Russian side the Leningrad Oblast is relatively wealthy by Russian standards,

but is primarily focused towards the city of St. Petersburg, while the Pskov

Oblast on the southern part of the border with Estonia is rural, and one of

the poorest regions in all of Russia. All of the regions in question, except

the Leningrad Oblast, have experienced economic growth rates below the national

averages.

The demographic make-up of the southern regions on both sides of the border

is moving in the wrong direction, as young people tend to move away to areas

with more job opportunities. In the northern regions Ida-Virumaa the population

has held slightly more steady. This can, however, be partly ascribed to its

relatively low level of integration with the rest of the country. This region

is overwhelmingly populated by members of the Russian minority, whose mastery

of the Estonian language is often rather poor.

Crossborder cooperation between Estonia and Russia has been relatively

limited since 1991, as it has tended to run foul of various obstacles created

by the poisonous political relationship between the two countries. The rather

different outlooks of the regions on the two sides of the border has also made

cooperation harder. This is particularly true of the northern case where the

Leningrad Oblast is directing its main activities towards St. Petersburg, and

thus being less focused on engaging with Ida-Virumaa. Among the southern regions

cooperation has been somewhat deeper, including the formal establishing of a

euroregion in 2003, but is still at a relatively low level.

Bilateral economic relations have also been fairly underdeveloped in the years

since 1991. This is - or was initially at least - partly a by-product of the

general economic transition both countries went through during the 1990's, as

their exports became less competitive in the free market. Also, Estonia very

soon oriented its foreign and economic policy towards Western Europe, thus deliberately

prioritising closer relations with the European Union. Problematic for the development

of trade was also the Russian policy of 'double tariffs' on both imports and

exports from Estonia. The combined effect of these factors has been that Russia

is only Estonia's fifth largest trading partner, and only supplies a very minor

proportion of FDI into Estonia.

Bilateral trade has however been growing rapidly since 2004, when Estonia joined

the European Union and its Common Commercial Policy. At the same time Russia

has negotiated closer economic agreements with the EU, which was also extended

to Estonia in 2004, thus abolishing the 'double tariffs' regime. Bilateral trade

has as a consequence of these developments more than doubled during this time

period, and there is every reason to believe that this trend will continue.

Security at the border has been very strict since 1991, something which Estonian

officials put down to their experience with Russian organised crime. This "unreasonably"

harsh policy has been effective in steering most forms of crossborder crime

such as smuggling (including illegal drugs), illegal immigration and human trafficking

away from Estonia.

Physical security is converging to the standards set by the Schengen agreement,

with Estonia expecting to join the Schengen zone in 2008. In enforcement the

movement is towards a greater reliance on technology rather than paure manpower.

Cooperation with Russian authorities has generally been good, and has especially

become more developed in the last 5-6 years.

A series of major disputes are still going on between Estonia and Russia, which

tend to sour bilteral relations. Some of these relate to different interpretations

of the Soviet occupation of Estonia between 1940 and 1991. Another, related,

problem is the lack of a treaty regulating the border between the two states.

A treaty was negotiated in the 1990's after Estonia dropped its demand for certain

of its former territories, which had been transferred to the Russian SSR during

the 1940's. This treaty was finalised in 1999, but has for purely political

reasons not yet been ratified. A third major problem area is the dispute over

the status of the ethnic Russian minority in Estonia. These arrived during the

years of occupation, and has subsequently to Estonia regaining its independence

had to qualify for citizenship through a standard naturalisation process, leaving

a large number without any formal citizenship at all. The integration of this

minority into Estonian society is an ongoing process, but is also a very sensitive

subject for Estonians and non-Estonians alike.

Summing up, one can conclude that many issues relating to crossborder communications between Russia and Estonia tend to get caught up in the generally poor political relations between the two countries. On the local level, however, authorities tend to find pragmatic solutions to issues of common interest when they can get to deal directly with each other. At the same time the increased involvement of the European Union in many policy areas has tended to depoliticise some of the thorny issues, thus effectively reducing some of the obstacles for better relations.